The van life is built for pandemic-infused summers; outside, away from crowds, and a parking spot next to the upper Miño to watch the birds and fish.

Sacral philomath; semi-permanent vision quest

The van life is built for pandemic-infused summers; outside, away from crowds, and a parking spot next to the upper Miño to watch the birds and fish.

As I rest my brain from reacting to the failed state of the United States; its ineptitude at controlling the coronavirus given ample time, money, and other country’s experiences to prepare, rising unemployment, continuing police brutality against people of color, and an uninspiring democratic challenger, I look toward things closer to home. My partner, who is Spanish, cares little for politics and I truly can’t blame her. But in the interest of things Galician, especially written in English, I’d like to preview the upcoming regional elections this year.

Election Day is today, when people head to the polls under less-than-ideal circumstances. The elections were supposed to be held in early April, alongside the Basque Country (Euzkadi) elections. President Feijóo postponed them due to the coronavirus pandemic. Vote by mail requests nearly doubled from 2016 for obvious reasons. For Americans who are used to years-long affairs, these are quite short. I only started noticing campaign posters two weeks ago.

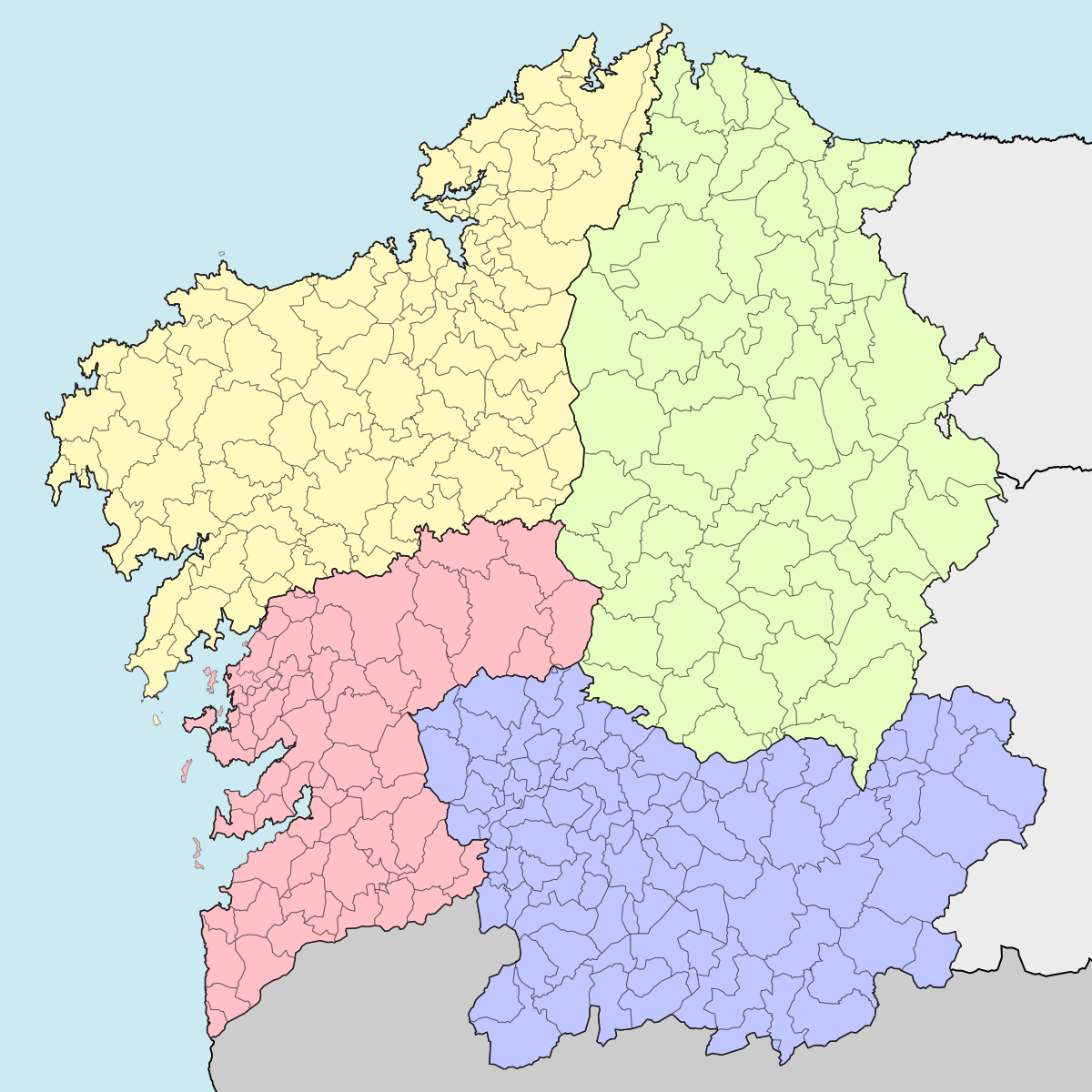

There are 75 seats in the Galician Parliament for the four provinces. Each province gets 10 seats with the remaining 35 distributed according to population. In the last regional elections in 2016, the seats were distributed thus: A Coruña (25), Pontevedra (22), and Lugo and Ourense, our province (14 each).

Every party puts forth a list of candidates for each province, with their respective head of list, cabeza de lista, as their priority candidate. After the votes are tallied, parties are awarded a number of escaños, seats in the Galician Parliament depending on its vote share. If a party doesn’t cross a 5% vote threshold in that province, they don’t win any seats.

Other than being a multiparty parliamentary system, what interests me is this list system. Voters vote party, rather than a particular candidate. And a head of list or other candidate could theoretically win a seat to represent the province by voters from out of their immediate area.

There are numerous parties contesting the Galician elections in 2020 and I’ll highlight a few of them.

The Popular Party of Galicia is the conservative, center-right party that has governed Galicia since 1989 aside from 2005-2009, when a coalition between PSOE and BNG briefly held power. Unfortunately, Alberto Núñez Feijóo, the current president, is expected to retain an absolute majority, despite his old ties to a Galician drug smuggler, despite funding cuts to public education, despite cuts to public health, etc.

The Socialists’ Party of Galicia, like its national formation which heads the Spanish Government in coalition with Unidas Podemos, is not much socialist as it is the traditional center-left party. Think Democrats, my Yankee readers. While it is true that they defend universal public health, there are still elements within PSOE who are very amenable to business and capital. Gonzalo Caballero from Pontevedra has been leader since 2017. Without reading up on him so much, he seems to have become leader in circumstances like president Pedro Sanchez, that of a prodigal return.

The Galician Nationalist Bloc is a at once a left-wing and nationalist party with Ana Pontón as its spokesperson. Different than the Catalan independentists, BNG calls for further autonomy for Galicia, recognition as a historical nation within Spain, and promotion of the Galician language. It was formed in the eighties by communist and socialist parties that were in favor of more home rule for Galicia. After reading even a quarter of Castelao’s Forever in Galicia, I am pretty partial to his and their ideas of true federalismo, something that a plurinational Spain would do well to adopt to better serve its diverse population.

Galician in Common-Anova Mareas is the Galician left-wing coalition of Unidas Podemos, the once-fabled protest-turned-party that burst onto the electoral scene with wins in the 2014 European Parliament elections. Democratic socialist, anti-austerity, left populist. The national party are in coalition with PSOE in the national government and Communist Party and United Left ministers Alberto Garzon and Yolanda Díaz being in government is a good thing. The Galician bloc has incorporated various municipalist movements, or tides, mareas, from the 2015 local elections. After former spokesperson in Congress Yolanda Díaz joined the government, Anton Gómez-Reino from A Coruña has been at the helm. Unfortunately for Unidas Podemos at the national level and Galicia en Común at the local level, support has diminished in favor of PSOE and more probably BNG

There is of course Vox, the far-right illiberal party that became a powerbroker in the Andalusian elections of 2019 and helped the first non-socialist Andalusian president gain power there. Anti-immigrant, deniers of gender violence. A lot has been written about Vox’s threat to Spanish democracy in the international anglophone press. Since it is my blog, I don’t need to be impartial. They are like those Americans who call millennials snowflakes, threaten people of color and immigrants with violence, cry wolf about how they are being censored, that there is a vast conspiracy of globalists, that there is a culture of silence and Spain must return to some form of proto-fascism. They are disgusting.

Cidadáns, the Galician arm of Ciudadanos, or Citizens, is also a recent neoliberal party originally formed in Barcelona. Originally billed as a social Democratic party, the party has swayed left or right based on political calculation and what alliances seem to be prudent for the party given each election. The formation collapsed at the last national elections and Albert Rivera resigned as party head. I’m not sure how much support they have in Galicia. We’ll see.

We won’t know for sure until after all the ballots have been tallied, but all major polls point to another absolute majority for PPdeG and four more years of Feijóo. What is more uncertain are a few things.

After some deliberation, I’m moving links off of the main page. While I have added a menu option for links that is more prominent and they will still appear in the RSS feed, I removed them for a couple reasons. They are usually not directly related to the photos or journal posts and they are often extended quotes with a bit of my own commentary.

But that won’t stop me from sharing what I read. With reduced time in the my own vampire castle, I prefer the open spaces of the independent web even more.

I might occasionally bundle some diverse links together without any relation to each other, which is pretty in-character for me. But not today.

Amandla Thomas-Johnson, a Dakar-based journalist for Middle East Eye, is very reliable for Mauritania news in English. His piece about five Republican congressmen’s letter to the Secretary of State Pompeo warning of the human rights situation could be a good place to start for people unfamiliar to the country’s issues.

These efforts to lobby what are two of the country’s most stalwart allies come as Mauritanian activists make renewed calls for the government to address racial injustices amid a global groundswell of Black Lives Matter protests.

Mauritania is a key ally for the United States in its ’war on terror’ and hosts the second-largest diaspora community for Mauritanians, despite Trump’s ICE going after some of them.

Mauritania has a deep racism problem embedded into the fabric of society, so much so that even well-meaning people who are not subjected to second-class citizenship often fail to see the problem. Does this remind you of another country? I should hope so.

The congressmen’s letter said: “Mauritania has a long history of hereditary slavery based on ethnic and racial discrimination against Black Mauritanians.” The country formally abolished the practice in 1981 but criminalised it only in 2007, and in 2018 the Global Slavery Index estimated that 90,000 people in Mauritania were living under modern slavery.

On top of the vestiges of slavery that does not look like the chattel plantation slavery system of the America, Mauritania

The congressmen also criticised the lack of accountability for purges by state forces of Black African Mauritanians between 1989-1991, in which tens of thousands – about eight percent of the community – were deported or forced to flee to neighbouring countries. “Mauritania has not provided accountability for mass murders, repression and unwarranted deportations,” their letter said.

Most of those purged from the country were subsistence farmers working on the little arable land Mauritania has, which lies along the Senegal River valley in the south. Others were intellectuals, businesspeople and professionals, members of the thriving urban elites who were pushed out as the government pursued a sectarian Arab-nationalist ideology.

Black Africans make up about a third of the country’s population, as do Arab-Berbers, the dominant group. Haratin, the Black descendants of slaves once owned by Arab-Berbers, account for the rest.

Despite the violence, a law was passed to shield the perpetrators from justice and an amnesty was granted to the security forces involved.

Mauritania has been described as the other apartheid for its treatment of Afro-Mauritanians. As many in the the United States wake up to our own failings, it’s a small but positive step that some in Congress, from the own president’s party no less, are speaking up.

I’ve often seen these towers in the distance while walking in the monte but didn’t know this was Penamá, most likely the highest point in the area.

We woke up earlier to avoid the heat and hiked 2 hours to reach its “peak”, which was mostly flat and without any spectacular views, at 927 meters (3041 feet) above sea level.

The village thirty minutes down, however, has a great lookout and we even saw what most be Ourense.

I didn’t take many photos but did get this later in the afternoon while in town.