I finished the first chapter of Shahab Ahmed’s What is Islam, where he lays out the need for a rethinking what should be considered Islam (for the academy and as a theoretical-object), introduces his Balkans-to-Bengal complex, and presents six questions that he expands on in the book before concluding with a chapter synthesizing all of the work into his reconceptualization.

There are so many things that interest me about it. For starters, it’s practically an encyclopedia for modern scholarship on Islam, Sufism, and the sharī’ah.

It’s also a confirmation from someone outside myself (with my internal biases of my race, class, and experiences) that accepts questioning our modern conceptualization of Islam, which almost totally emphasizes the juridical aspects while relegating the mystical or simply the less orthodox aspects and histories, as valid and worthwhile. Here’s one quote from page 125:

Given that modern man is, to a historically unprecedented degree, homo juridicus, it is hardly surprising that the leitmotif of Muslim modernism of every stripe is the assertion of the unilateral normative supremacy of something called sharī’ah identified with law—whether that sharī’ah/law be in some pristine or reformed condition. It is striking that so much of the discourse of modern reformist Muslims—who have, for the most part, received the norms of modernity second-hand and by the forces of arms and coercive administration of European colonialism—about (what is) Islam has been about rethinking the Islamic state by rethinking Islamic law, and not about rethinking theology, philosophy, ethics, poetics, and Sufism as a hermeneutical means to modern Islamic norms. The relative lack of concern on the part of even the most self-consciously critical modern Muslims to re-think or re-form normative Islam in terms of theology, philosophy, and ethics—let alone Sufism and poetics—is one of the most peculiar, but also symptomatic, elements of Muslim modernity as modernity.

But in regards to this post, it just makes me ache for Istanbul, Bursa, and Konya; the mosques, the narrow streets filled with cafes, the tram running through İstiklal Caddesi, Rūmī‘s mausoleum, the bookstores. It was the first vacation that Patricia and I took together during one Christmas break from school. Here’s a few of the many photos I took from December 2014.

I took this photo of Masjid Sultanahmet’s entrance with an iPhone 5S and it blew my mind.

When I went to pray, I was dazzled by the stained glass and inscriptions all over and the illumination from the lights overhead. In Mauritania and Sierra Leone, mosques are a nondescript affair with hardly any decoration to them.

I can’t remember the name of this neighborhood but it was close to the Bosphorus bridge.

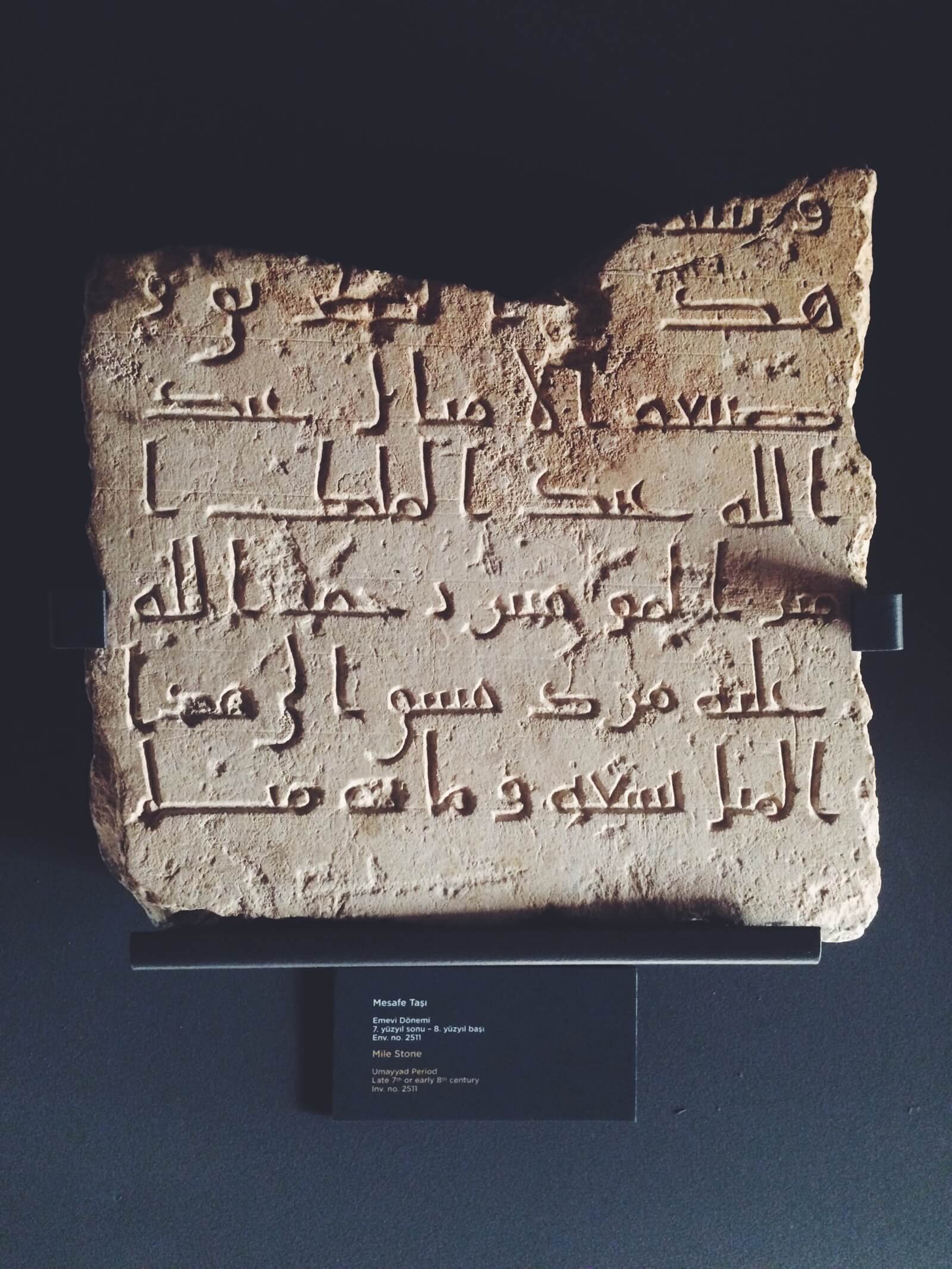

So many museums. In the Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum, I learned much more about the major and minor dynasties; the Rāshidūn, the Umayyads, the Abbasids, the Fatimids, the Almoravids, and the Almohads.

On Christmas Day, we were in Konya, the adopted hometown of the Persian poet Jalāl ad-Dīn Rūmī. I felt we were the only western tourists there at the time. The museum and mawlana’s mausoleum were free that day. After, I went to the noon prayer at the adjacent mosque. It was under construction and covered in a blue tarpaulin but the rugs and chandelier were still very nice.

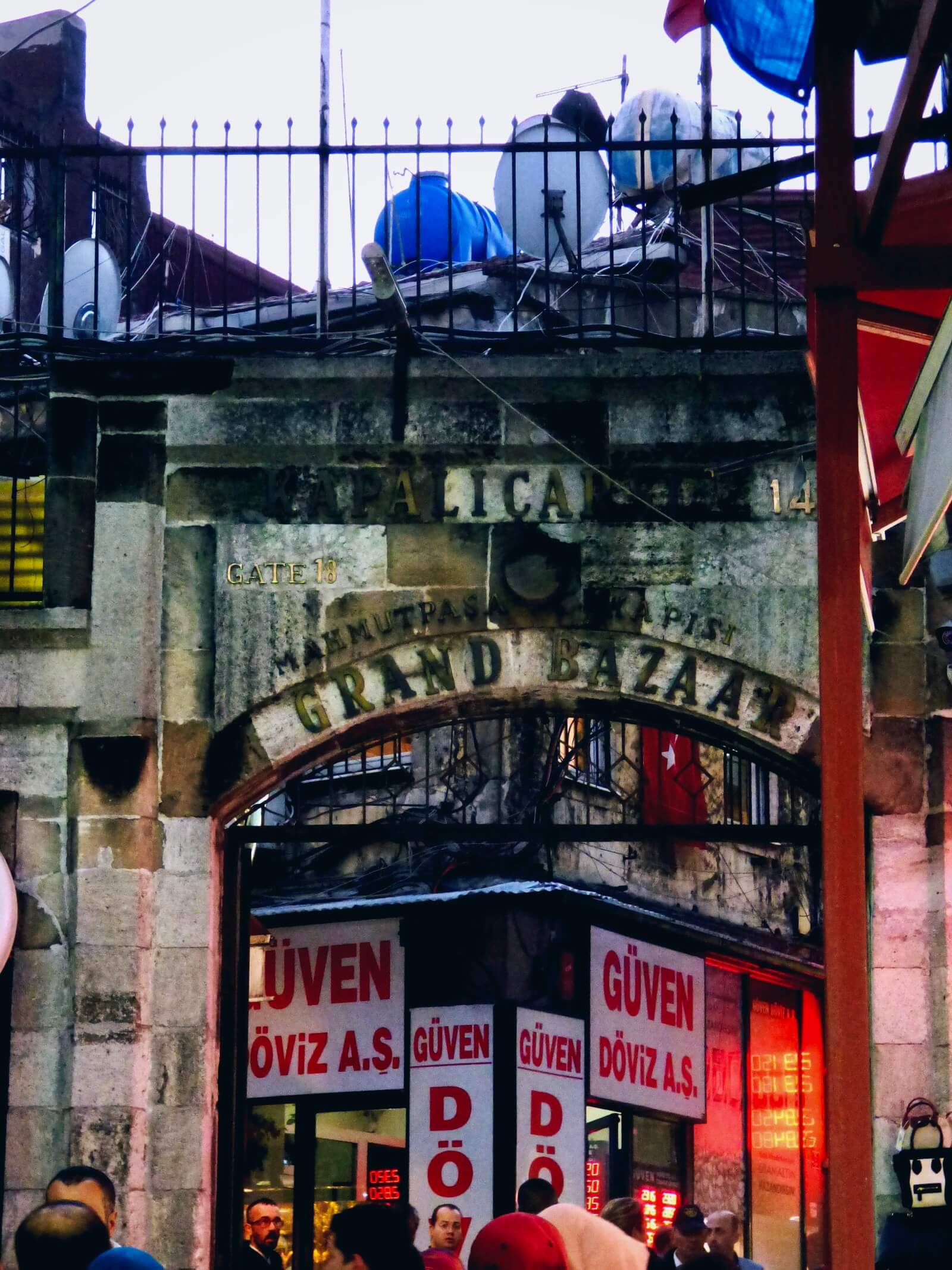

After taking the train back to Istanbul, we visited the Grand Bazaar. Walking anywhere in Istanbul was so pleasant, though cold. Coming from the climate of the Saharan edge of Nouakchott, it was a bit of a shock.

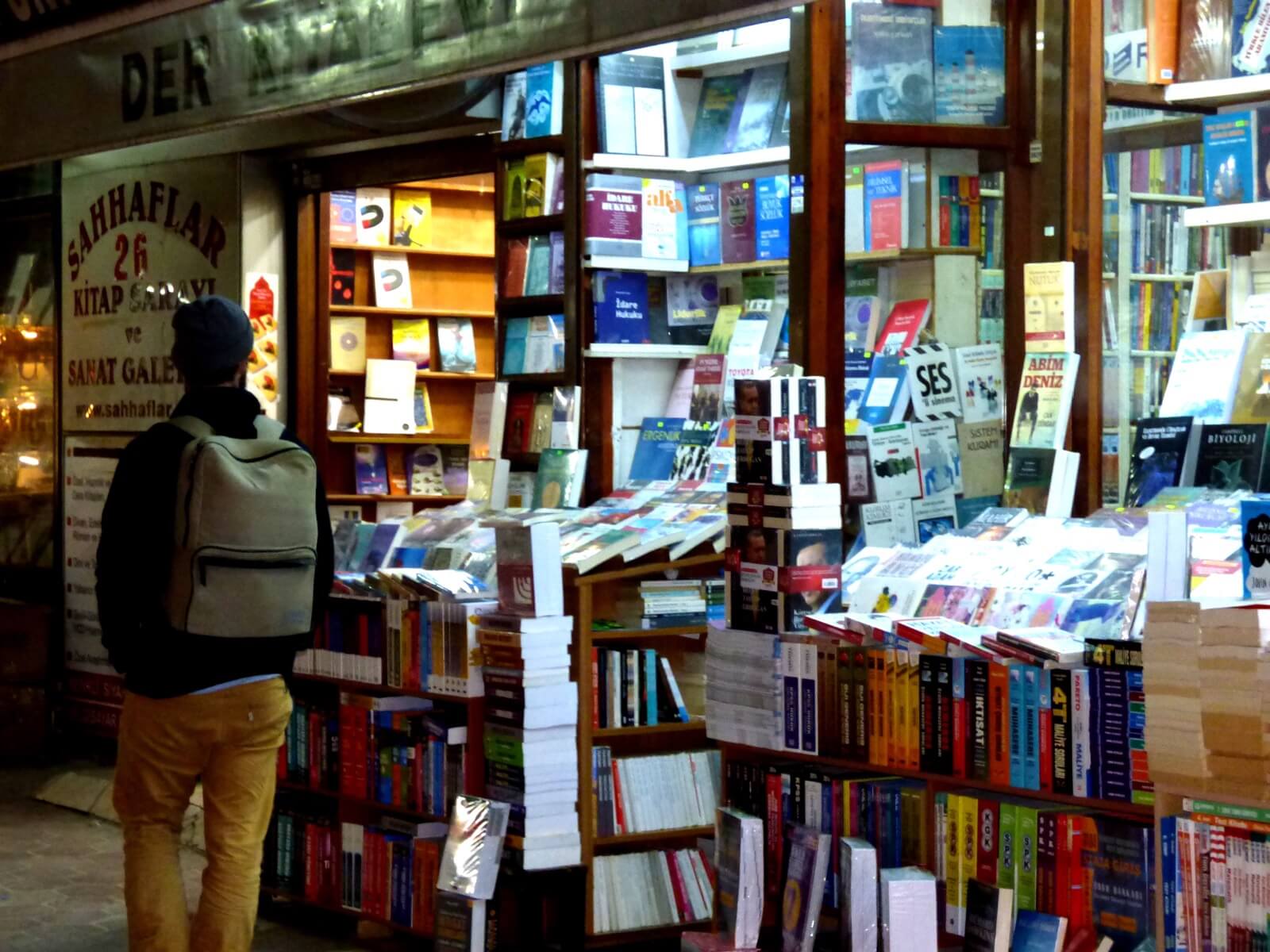

I can’t remember the street but this one with bookstores everywhere was pretty special. Most of it in Turkish and Arabic, I actually purchased two books in a different bookstore in Fatih. Both were histories:

- John Julius Norwich’s A Short History of Byzantium which I never finished. Most of it was court intrigue and what dynastic family plotted to kill the emperor at the time. Meh.

- Jason Goodwin’s Lords of the Horizons: A History of the Ottoman Empire was incredible, however. Short, concise, but almost un-put-down-able. That’s when reading history clicked for me.

It’s hard to know if and when I’ll return to Istanbul. While a few bombings occurred later in the next year, at the peak of the so-called Islamic State, now traveling seems so far away in our new age of pandemic. But I remember it fondly and that will have to do for now.