We returned from a short trip a few days ago with Alqo and the van, through the center of Galicia. We were there to look at towns, try to picture ourselves there, and talk to people and inmobiliarias to see if there were any decent opportunities to rent a house.

Those who have visited Spain can tell you about the overwhelming number of se vende signs, especially outside of Barcelona and Madrid (but we were in search of something que se alquila).

A byproduct of rural depopulation, some pueblos now are only populated by a handful of retirees. Those concerned with cultural heritage are worried that as locals age, historic buildings, archaeological sites, and churches will fall into disrepair with no one to preserve them. Schools in the mountains on the border of Portugal are being converted into centros de tercer edad. The jobs and cultural life that young people need and desire is not there. And so, they leave.

Nowhere was this more apparent to me than the province of Ourense. The only Galician province without a coastline, Ourense has the lowest birth rate in Spain. But Ourense also has its own Grand Canyon with the Cañón do Sil, beautiful meandering rivers like the Miño and Arnoia, and a pleasant and walkable eponymous capital with world-famous thermal baths.

If you read my other post, we were initially looking for things around A Estrada and Lalín, sizeable towns in the center, close to all the provincial capitals. But when we arrived in Chantada for for a roadside homemade lunch, we had to make a decision; turn north to Lugo, or south to Ourense. Already a bit chilly in late September and already expected in Senderiz to meet up with Edo from Sende, we both agreed; south.

And we’re extremely pleased with ourselves that we did. Because what we found there and what we learned about ourselves, our preferences on environment and community, and the future we want exists in Ourense province.

Not to degrade the towns we had already passed through, but there wasn’t anything calling us to them. They were simply mid-size towns. But that changed when we saw the two medieval Ourensan towns of Ribadavia and Allariz.

Alongside the northern bank of the Miño sits Ribadavia. The center of the Ourensan winemaking industry, the town also had a significant Jewish community, almost half the town by the 14th century, until the Inquisition came.

Outside of a day in Lugo and a few evenings in Pontevedra, I hadn’t seen a casco antiguo in Galicia and what a difference it makes upon seeing a town for the first time. Once we arrived, we walked by the old Castelo de Ribadavia and through the barrio xudeo, ordered vegetarian dürüm from a Turkish restaurant, and sat by the river while Alqo tried to eat bees, which seems to be his new favorite hobby.

After a few hours or wandering around, through the town and near the river, we found an inmobiliaria who had exactly one rental listing; a small house in a parroquia of Ribadavia about a kilometer away. Satisfied we had at least found something, we were given a tour by the agent. Though it was in a wonderful location, with easy access to the town using a walking and bike path by the riverside, there wasn’t much land to start a garden nor a chimney or wood-burning oven.

We then turned our attention to a town not at all on our radar; Allariz. My mother-in-law had mentioned Allariz in passing years ago, remarking on its beauty and how much there was to do in the summer. Only 40 minutes from Ribadavia to Allariz via Ourense, we stopped in the capital to buy some groceries and arrived in the early afternoon.

Like Ribadavia, Allariz has a casco antiguo that is incredibly well-preserved. The banks of the Arnoia have been turned into playgrounds, rest areas, and walking paths to enjoy the scenery of the river. Originally the town was built near a castro, those pre-Roman Celtic settlements. It played a major role in defending southern Galicia from being absorbed into Portugal and also held a sizable Jewish community (who were prohibited from living outside of the judería in the 13th century).

But unlike Ribadavia, Allariz seemed more alive. Granted, it’s difficult to take my impressions literally. Since we have our own vehicle, we occasionally arrive to a town during siesta time, when shops are momentarily closed and people are back home eating lunch or engaging in sobremesa with family or guests. Regardless, to me, Allariz seems to have an abundance of cultural events, civic institutions, herbolarios, and other interesting stores and places.

Allariz has been governed by O Bloque Nacionalista Galego, the Galician Nationalist Bloc, for thirty years. And it shows. Even amongst apoliticals around Pontevedra, when we mentioned Allariz, they said how well-known Allariz is for O Bloque’s commitment to social and economic wellbeing and to city preservation.

And like Ribadavia, we found exactly one rental. A couple kilometers outside of town and without much of a garden, we both feel more confident that once we have moved there, more things will become available, maybe even a few casas a reformar to buy, and to start the homeowning project. But all in good time.

For now, I’m motivated by our decision to check out Ourense, and our options, even though they are somewhat limited. I haven’t even had time to write about our experience in Sende. Another time, then.

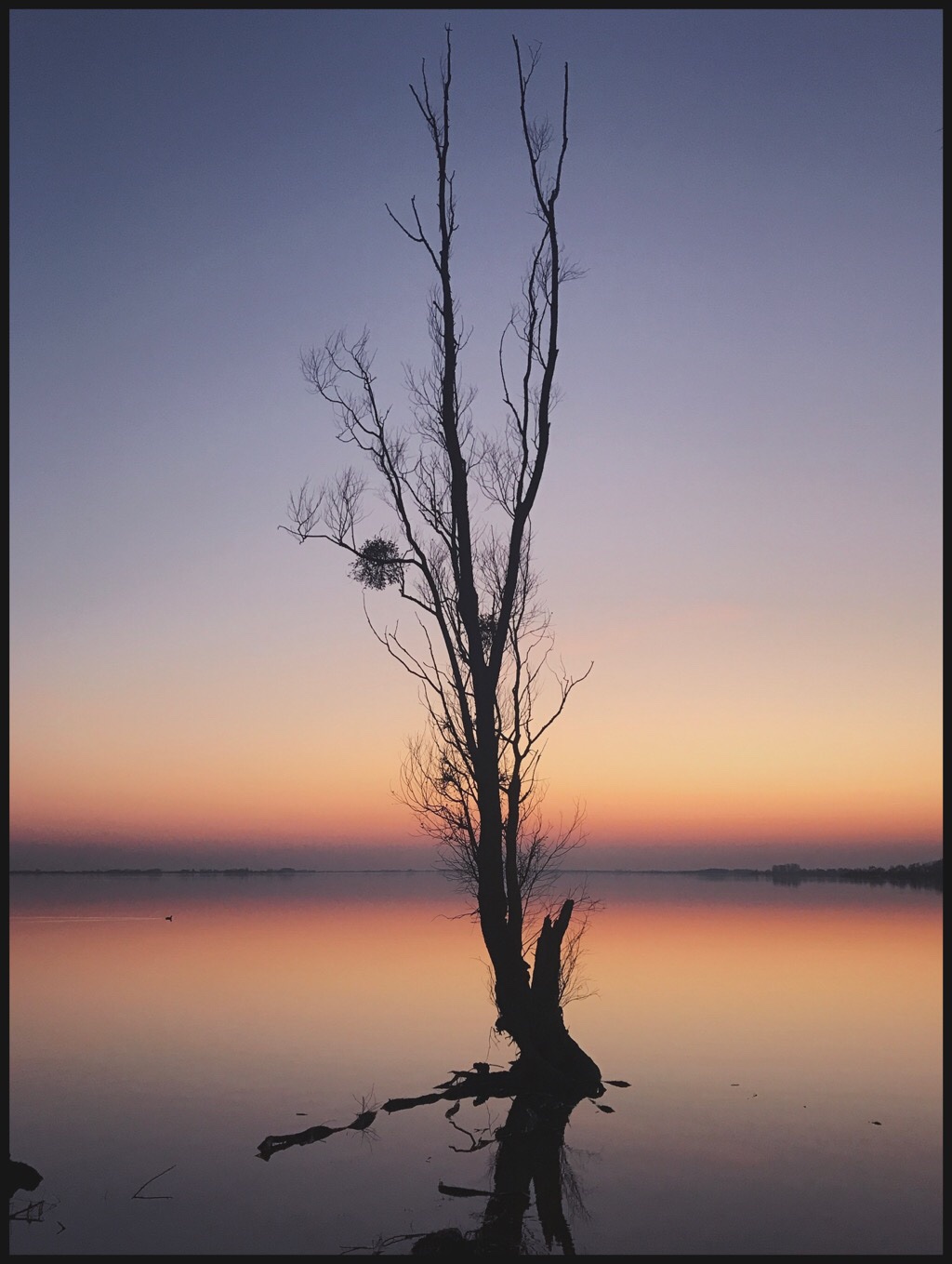

But here’s a photo of the climate strike in Pontevedra.