Israel asasina, a Xunta patrocina

Israel murders, the Xunta sponsors

No sur de Lugo e noutros lugares de Galicia, seguimos manifestando contra o xenocidio e apartheid israelí e apoiando a liberación de Palestina.

Sacral philomath in unruly reverence

Israel asasina, a Xunta patrocina

Israel murders, the Xunta sponsors

No sur de Lugo e noutros lugares de Galicia, seguimos manifestando contra o xenocidio e apartheid israelí e apoiando a liberación de Palestina.

I would love to sit down and write a post about leaving Allariz as well as share news about our progress here, but there’s tons to do and I always have to push back writing. Let this photo of the valley of Lemos suffice for now.

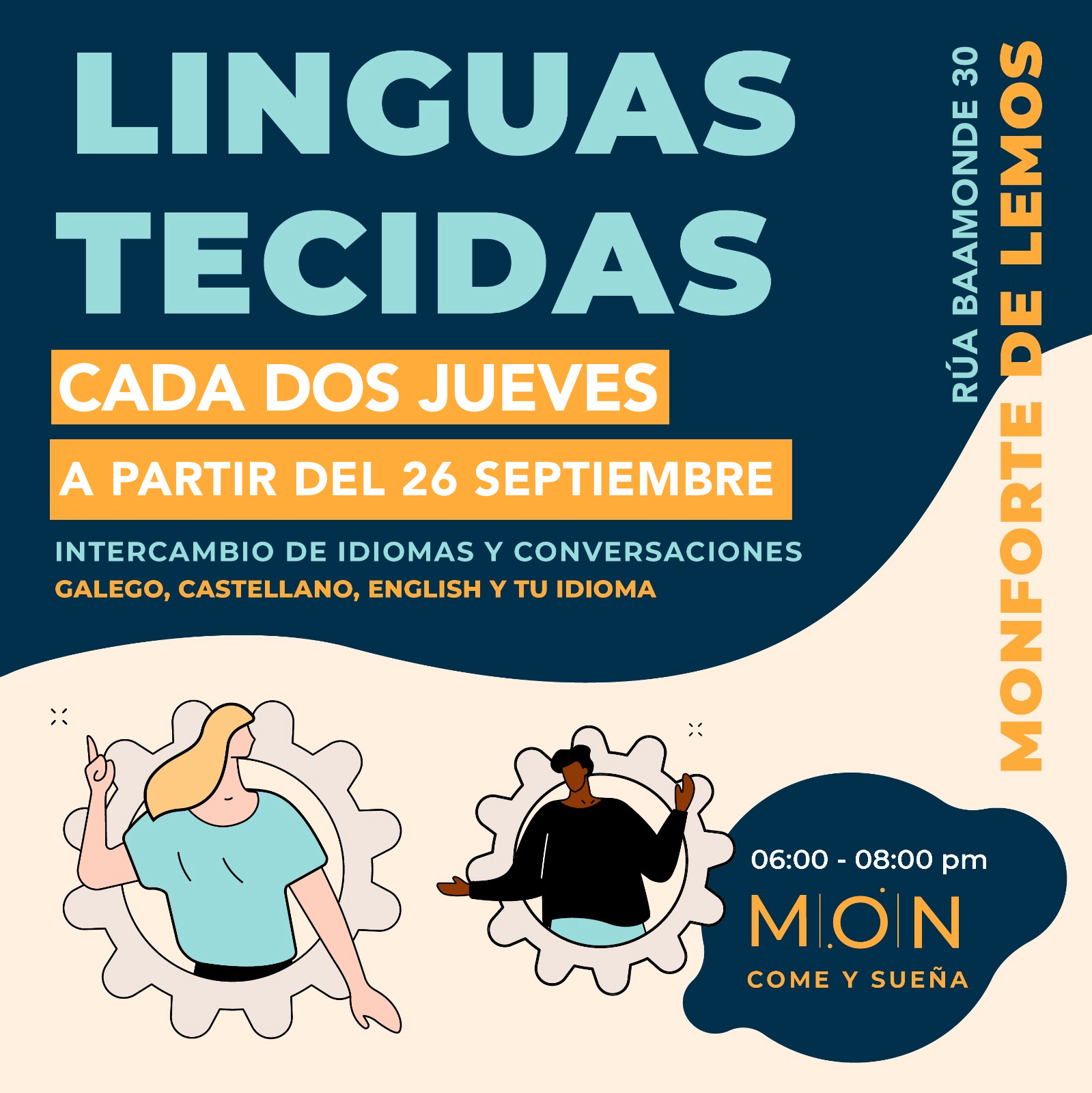

I’ve been internet absent for a while but everything is good over here, all told. Our house search is finally over. A couple weeks ago, we bought a small late 18th-century stone house with some adjacent ruins. They sit on 1,800 square meters of land in a depopulated village close to Monforte de Lemos, a town of around 20,000 and the capital of Ribeira Sacra. The area is filled with oak, chestnut, cork, and other plants native to Galicia, as well as pine for paper pulp.

It’ll be a few months before we’re able to leave our rental in Allariz. So on Wednesdays, our day off, we drive the hour up on truly one of the most beautiful drives I’ve ever seen in Spain and do whatever we can.

Yesterday, it was sweeping, fixing the door, and temporarily closing one of the windows so we can start storing tools there.

Bo Nadal, everyone!

I’m becoming an expert of the towns in southern Lugo. Silleda, Melide, Bóveda, Pantón, Sarria, Láncara, O Incio. But before we left a week ago to celebrate Patricia’s mother’s birthday, we thought we were going to A Coruña to visit Fragas do Eume, or perhaps some of the province’s incredible beaches and forget about fincas and casas rústicas.

Nature had a different plan for us, however. The tropical storm Kyle came, producing an almost ciclogénesis explosiva. Next, we thought of heading east towards the Navia Valley in Asturias (which Galicians consider as part of Galicia or Galicia estremeira) but short on time and in a different mood, we decided to stay closer to the area between Sarria and Monforte de Lemos.

After a day or so around Silleda and Melide, and learning about marian apparitions, their inspired movements, and seeing el Santuario de la Saleta, we started visiting some of our favorites from idealista, the zillow/Redfin of Iberia.

And as probably anyone who has been in a position to buy land or a house can tell you, it is not a walk in the park.

There have been a few places, affordable for us to in need of lots of time and work to make them habitable, with their different and respective pros and cons.

While all of these were special in their own way, we’ve also talked to owners and neighbors who have different pieces of advice for us; don’t restore, it’s a money pit, build something new, etc. All of which is great advice but produces a headache and a feeling of vertigo in the beginning of this process.

Whatever happens, it will be a long process. But one advantage of this impromptu trip was solidifying our search area. Now, it’s time to talk to an expert in bio-construction, as we continue to dream of an ecological, and economical, project.