“I want to do whatever it takes to make it possible for everyone, around the world, to enjoy a life worth living.” — Who Owns Tomorrow? by Chloe Watlington in Commune

It is May of 2010 and I’m back in California going through a range of emotions; leaving my university life in Oregon, understanding that a short, failed relationship I spent two years desiring was not reciprocated, and the uncertainty of committing to 27 months abroad before I return.

In a Borders Books next to my parents’ house, I play a game; only perusing the Penguin Classics, the spines uniformly with white text on a matte black. Hundreds of them scattered alphabetically over the store. One sticks out with the the title A Little Larger than the Entire Universe. Already deep into vague misreadings of quantum physics and squaring it with Islam, it sounded like something in my wheelhouse. Fernando Pessoa, an unfamiliar name of a famous 20th-century Portuguese poet. The translator and editor of the poetry anthropology in my hands wrote:

Instead of getting down to the practical business of living, he continued to wrestle with theoretical problems and the big questions: the existence of God, the meaning of life and the meaning of death, good vs. evil, reality vs. appearance, the idea (is it just an idea?) of love, the limits of consciousness, and so on. All of which was rich fodder for his poetry, thriving as it did on ideas more than on actual experience.

The intervening years since stumbling on his work have been full of migration, learning, love, faith, and adventure but also of ambiguity, uncertainty and difficulty. But editorial impression, of a life not fully lived but wholly examined and possibly being paralyzed by it, has served as a bizarre measuring stick to my own. I’m infatuated by the written word, of outside perspectives to better understand the world and my place in it. But how far does one accept outside stimuli to live a life?

My active, outside, rural years in Sierra Leone stand in sharp relief to the introspective and inside ones in Mauritania. I’m an extreme person.

I don’t envy Pessoa. He died an alcoholic having rarely left Lisbon after returning from Durban in his teenager years. I left Mauritania to win back my personal relationship with the Divine, away from the legalism and minutiae of a nominally Muslim society. Distance made the heart grow fonder, it seemed. In the wintry Andes and with a few entheogenic plant experiences, I felt reawakened and clear-eyed.

Now it is 2019. Now surrounded by the modern city life, I feel too tuned in to what is happening in the world. And it looks grim.

There are some who say we are doing much better than we ever have in human history. Then why does it feel so shitty?

Climate change, the normalization of racism and xenophobia, rising inequality and our potential responses are our generation’s World Wars or Paris Commune. Just as Rumi’s family anguished and migrated to escape the world-ending devastation of the Mongol invasion, we have our world-ending scenarios that we must face.

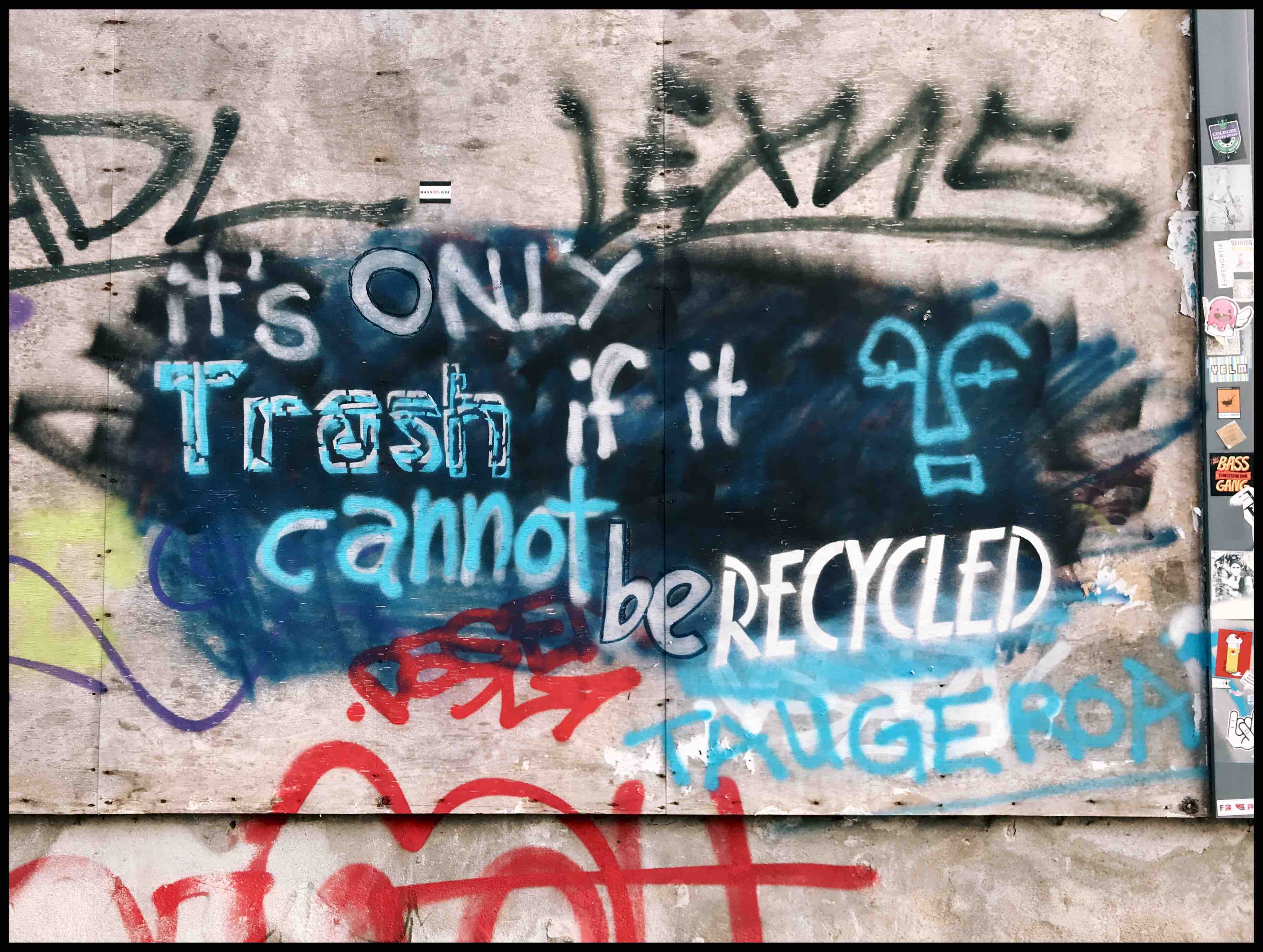

We must educate ourselves and others. We must reject false choices and centrism. And then we must organize ourselves accordingly in a way that respects and protects all life from the fevered egos that see the world as a zero-sum game.

I become more class conscious and eco-conscious by the day. I’m an extreme person. No longer does it seem right for me to travel around on planes as often as I did. Or buy everything wrapped in plastic, the micro-remnants of which are now in almost every living being, when a bit of planning and with the abundance of alternatives.

With time comes more understanding and responsibility.

“I take my desires for reality because I believe in the reality of my desires.” — Paris, May 1968

I add the words hope in the late anthropocene to the existing tagline at the top to reflect my desires in this reality. I commit myself to working on solutions and not adding to the despair.

Thanks for reading, seriously.